Tomato plants are susceptible to a variety of diseases that will impact their health and productivity.

Following are some common tomato plant diseases.

Their descriptions, causal agents, symptoms, disease cycle and management:

Early Blight (Alternaria solani):

Early blight is a fungal disease that affects the leaves, causing brown to black spots with concentric rings. It can also affect stems and fruit. Infected leaves may eventually yellow, wither, and drop prematurely. Proper spacing, removing infected leaves, and applying fungicides can help manage early blight.

Causal Agent

Early blight disease affects tomato and eggplant, but not pepper. It is caused by the fungus Alternaria solani. Potatoes are also susceptible to early blight.

Symptoms

Lesions can develop on leaves, fruit, and stems. The first foliar symptoms are brown necrotic spots on older leaves that enlarge. Younger leaves do not show visible symptoms. A yellow halo may develop around the lesions, and concentric rings develop when spores are produced. When there are numerous or large lesions, the entire leaf may become yellow and fall off, exposing fruit underneath to potential sun-scald. Infections result in reduced yield and lower quality of fruit. Seedlings can develop stem infections. Infected seedlings planted in the field either die as stem lesions enlarge or the plants may be stunted and unproductive. Fruit may also be infected. Lesions on green or ripe fruit develop near the calyx end and become leathery over time.

Disease Cycle

Optimum conditions for infection occur during warm (78-84⁰F), wet periods of rain, overhead irrigation, or heavy dew. The fungus survives in plant debris in the soil (main source for inoculum) and on seed. After landing on tomato plants, spores only require two hours to germinate and infect the plant. Lesions become evident two to three days later. Spores develop on lesions and are dispersed by wind.

Management

- Use resistant varieties. ‘Mountain Supreme’, ‘Mountain Fresh’, ‘Plum Dandy’, ‘Mountain Magic’, and ‘Defiant PhR’ have resistance to the disease.

- Only use pathogen-free seed.

- Use Crop rotation. Rotate soil out of all solanaceous crops for at least two years.

- Provide good weed control and remove volunteer host plants (all solanaceous crops) this will help to reduce potential sources of inoculum.

- Keep plants vigorous through good soil fertility regimes.

Late Blight (Phytophthora infestans):

Late blight is a devastating disease that can destroy entire tomato crops. It’s characterized by dark, water-soaked lesions on leaves, stems, and fruit. Under humid conditions, a white, fuzzy mold may develop on the underside of affected leaves. Copper-based fungicides and good cultural practices are essential for prevention and control.

Casual Agent

Late blight is a disease that can infect many solanaceous plants such as tomato, potato, and solanaceous weeds, however, there have been no reports of late blight in pepper or eggplant. The disease is caused by Phytophthora infestans and is infamous for causing the potato famine in Ireland in the 1840s.

Symptoms

All above-ground parts of tomato and potato plants can become infected. Foliar infections start out as small, water-soaked lesions that enlarge rapidly and become pale green. Eventually the leaves dry up and die. Severely infected plants can die. On the underside of leaves, growth of a white mold becomes visible on the lesions. Infected green fruit has brown or olive-colored lesions and often develop a soft rot. Infected vines also rot and have a foul odor to them.

Disease Cycle

Infections occur during periods of cool, moist weather, when temperatures are between 66 and 72⁰F. Above 86°F, infections will stop, but the pathogen can still survive and cause new infections when temperatures again become favorable. Symptoms can occur within three days of infection and plants can collapse so rapidly that they may appear to have been damaged by frost (Stevenson and Bolkan 2014). Phytophthora infestans survives on volunteer tomato and potato plants, solanaceous weeds (for example, hairy nightshade and bittersweet nightshade), petunia plants, and in tomato and potato cull piles.

Management

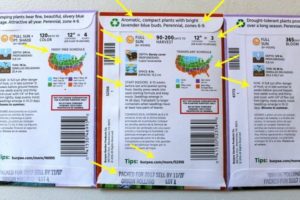

- Use resistant varieties. Burpee, Johnny’s Seed, and other seed companies have varieties with resistance to late blight including ‘Mountain Magic’, ‘Defiant PhR’, and the cherry tomato variety ‘Lizzano’.

Blossom End Rot

Blossom end rot of tomato is caused by calcium deficiency.

Symptoms

Brown, enlarged spots develop usually at the blossom end of the tomato or fruit, but can sometimes also develop in other areas or internally (without showing external symptoms). Over time, the lesions turn dark and leathery, and may be colonized by mold.

Management

Most soils generally have plenty of calcium and calcium additions are not recommended. Control blossom-end rot by using cultural practices that allow for proper uptake of calcium by the plant.

- Test soil before planting to determine if an adequate concentration of calcium is available.

- Use infrequent, deep irrigation to keep the soil uniformly moist and avoid water stress of fluctuating soil moisture.

- Consider using drip irrigation for more direct and uniform watering.

- Do not allow plants to be water stressed at night.

- Maintain even soil moisture by using organic or plastic mulch. Grass clippings/straw/etc. (2-3 inches thick) can be placed around the base of the plant to keep the soil cooler and reduce water loss.

- Avoid over-fertilizing. Do not use ammonium-based nitrogen fertilizers.

- Avoid injuring roots. Do not hoe or cultivate near plants. Pull weeds next to plants or use a plastic mulch.

- Do not overwater, especially in heavy clay soils.

Blossom end rot is a physiological disorder rather than a fungal or bacterial disease. It’s characterized by a dry, sunken, brown or black spot on the blossom end of developing fruit. It’s caused by calcium deficiency or inconsistent watering. Maintain proper calcium levels in the soil, provide consistent moisture, and mulch to prevent fluctuations in soil moisture.

Fusarium Wilt (Fusarium oxysporum):

Fusarium wilt is a soil-borne fungal disease that causes wilting, yellowing, and death of the lower leaves. Infected plants may die prematurely. There’s no effective treatment for infected plants, so prevention through using disease-resistant tomato varieties and practicing crop rotation is key.

Casual Agent

Fusarium root rot, caused by the fungus Fusarium solani, can infects the roots of peppers, eggplants, tomatoes, and cucurbits. F. solani has what are called “formae speciales,” (f. sp.) meaning that these types are very host-specific . For example, F. solani f.sp. eumartii infects pepper, tomato, eggplant, and potato, but does not infect cucurbits.

Symptoms

Infected roots will have reddish-brown lesions along the cortex of the main lateral roots. Vascular discoloration also occurs a few inches above and below these lesions. Foliar symptoms include interveinal chlorosis and necrosis, typically on a single branch. As the disease advances in the roots, the leaves of the entire plant will eventually turn brown and collapse.

F. solani can survive in the soil for 2-3 years without a host. The pathogen infects plants through root wounds and is most severe in temperatures ranging from 77°- 86°F.

Disease Cycle

Both fungi infect through roots. They grow through the vascular tissue up into the main stem. Wilting is caused in part by the fungal growth clogging the phloem and xylem and by the plant trying to stop the movement of the fungus by blocking the colonized vascular tissue.

Fusarium infections are favored by high soil temperatures (90⁰F) and high soil moisture. When the plants are dead, Fusarium oxysporum produces salmon-colored spores, called conidia, on the plant surface that are washed into the soil by rain and irrigation water. Fusarium also produces resting spores, called chlamydospores that can survive for several years in soil and plant debris.

Verticillium occurs more during cooler temperatures (68-74⁰F) and in soils with a high pH which are very common in Utah. It produces an overwintering structure (survival structure) called a microsclerotium, which is a hard black ball of fungal tissue that can survive for a decade or more in the soil, waiting for a suitable host to be planted.

Management

Both diseases are very difficult to control due to the production of the long-term survival structures in the soil.

- Use resistant varieties when available. Resistant tomato varieties are available for Verticillium race 1 but not race 2, and for Fusarium oxysporum races 1, 2 and 3.

- Plant on raised beds for better water drainage.

Verticillium Wilt (Verticillium spp.):

Similar to fusarium wilt, verticillium wilt is caused by a soil-borne fungus. It leads to wilting, yellowing, and necrosis of leaves. The fungus clogs the plant’s vascular system, disrupting water and nutrient flow. Crop rotation and selecting resistant tomato varieties can help manage this disease.

Casual Agents

There are two fungi that cause wilt of tomato, pepper and eggplant: Verticillium spp. and Fusarium oxysporum types called formae specialis. Both fungi are soilborne. The formae specialis are host specific. The one infecting tomato will not infect pepper or eggplant and vice versa.

Symptoms

Older leaves on tomato plants infected with Verticillium appear as yellow, V-shaped areas that narrow from the margin. The leaf progressively turns from yellow to brown and eventually dies. Older and lower leaves are the most affected. Sun-related fruit damage is increased because of the loss of foliage. A light tan discoloration develops in the vascular tissue, especially near the base of the plant. The discoloration extends a short distance up the plant and may occur in patches. Symptoms are most noticeable during later stages of plant development when fruit begin to size.

Disease Cycle

The fungus survives as microsclerotia in the soil. Once established in a field, it persists indefinitely and can cause disease whenever a susceptible host is planted. A large number of crops and weeds serve as hosts. The disease is favored by cool soil and air temperatures.

Verticillium wilt is difficult to distinguish from Fusarium wilt and positive identification may require cultivating the fungus in a laboratory. Verticillium wilt seldom kills tomato plants but reduces their vigor and yield.

Tomato Mosaic Virus:

This viral disease causes mottled or mosaic-like patterns on leaves, stunted growth, and reduced fruit production. Aphids can transmit the virus between plants. Controlling aphid populations, using disease-resistant varieties, and removing infected plants are crucial to managing the disease.

Tomato Mosaic Virus (ToMV)

Casual Agent

(ToMV) are two very closely related viruses with similar symptoms. Antibody-based molecular testing is necessary for accurate identification. TMV and ToMV are two of only a few plant viruses that are not transmitted by insects. In contrast to many other plant viruses, TMV and ToMV can survive for up to 50 years in plant debris and for weeks to months on trellises or wooden stakes.

Symptoms

Tomato foliage displays mosaic symptoms that can range from a faint light and dark green pattern to a darker yellow and green pattern. Mosaic symptoms depend on plant cultivar and temperature. Symptoms are fainter at high temperatures. Other foliar symptoms include leaf distortion (fan shape) and occasionally leaf curling. In some cases, fruit symptoms will not occur. In other cases, yellow rings or brown sunken lesions will show on ripe fruit, or the parenchyma layer of cells inside the fruit will turn brown. Because fruit symptoms can be mistaken for TSWV infection, the virus should be identified by a plant diagnostic lab.

Disease Cycle

TMV is transmitted by artificial grafting, and by contaminated seed. The virus can be spread on pruning tools or by bare hands, such as during sucker pruning or staking. The virus can also be spread by growers’ hands that handled tobacco cigarettes or chew that is infected with TMV. If seedlings are planted in pots or beds where previously infected plants grew, they can become infected. A common mode of TMV infection in greenhouses is through contaminated seed. Once the virus has entered the plant, through wounds as small as torn plant hairs, it spreads though the entire plant, including roots.

Management

Tobacco and tomato mosaic virus are difficult to control, as they can survive harsh conditions for many years. Once a plant is infected, there is no cure.

- Remove infected plants immediately. Do not compost infected plants due to the longevity of the virus.

- Use certified disease-free seed. When preserving seed from your own plants, do not keep seed from infected plants.

- Disinfect tools that came into contact with infected plant material. Reports from Florida indicate that dipping contaminated tools for one minute in a 20% powdered milk solution will kill the virus.

- Use new potting soil, pots, and string every time, when growing your own transplants, to minimize infection.

- Use resistant varieties.

◦ There are many TMV and ToMV resistant tomato varieties. Most heirloom varieties are susceptible to both viruses. The correct identification of the virus is necessary if resistant varieties are to be used. Some varieties are only resistant to one of the two viruses. Break-down in resistance of some tomato varieties to the viruses has occurred.

Septoria Leaf Spot (Septoria lycopersici):

Septoria leaf spot causes small, circular spots with dark centers and yellow halos on tomato leaves. As the disease progresses, the leaves may turn yellow and drop. Pruning lower leaves, promoting good air circulation, and applying fungicides can help control septoria leaf spot.

Casual Agent

Bacterial speck is caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato and only affects tomato. Infected tomato fruit is unacceptable for fresh market production, but fruit can be used for canning where tomatoes are peeled.

Symptoms

Tomato leaves develop small irregular shaped brown, necrotic lesions, often surrounded by a yellow halo. On small fruit (about 1 mm in size), round, black, superficial skin lesions develop.

Disease Cycle

The bacteria can be seedborne and can survive for at least a year in plant debris. There have been reports that the bacteria can also survive on weeds. Spread between plants occurs by splashing water from overhead irrigation or rain, by using contaminated tools, and by workers brushing along plants. Transplants in greenhouses may carry the bacteria on the surface without disease development. However, once the plants are in the field and environmental conditions are conducive to infection, the disease can develop.

Management

- Only use disease-free seed. When saving seed from plants, do not use seed from infected plants.

- Use resistant tomato varieties when available.

- Avoid overhead irrigation.

- Apply preventive copper-based bactericides. Once infection occurs, bactericides will no longer be effective.

- Remove plant debris and weeds.

- Rotate out of tomato for two years to non-host crops.

Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus:

This viral disease is transmitted by whiteflies. Infected plants exhibit yellowing, curling, and stunted growth of leaves, along with reduced fruit yield. Using insecticides to manage whitefly populations, practicing proper sanitation, and using reflective mulches can aid in prevention.

Casual Agent

This viral disease is transmitted by whiteflies.

Symptoms

Infected tomato plants initially show stunted and erect or upright plant growth; plants infected at an early stage of growth will show severe stunting. However, the most diagnostic symptoms are those in leaves.

Disease Cycle

Leaves of infected plants are small and curl upward; and show strong crumpling and interveinal and marginal yellowing. The internodes of infected plants become shortened and, together with the stunted growth, plants often take on a bushy appearance. Which is sometimes referred to as ‘bonsai’ or broccoli’-like growth. Flowers formed on infected plants commonly do not develop and fall off (abscise). Fruit production is dramatically reduced, particularly when plants are infected at an early age, and it is not uncommon for losses of 100% to be experienced in fields with heavily infected plants.

Tomato yellow leaf curl virus is undoubtedly one of the most damaging pathogens of tomato, and it limits production of tomato in many tropical and subtropical areas of the world. It is also a problem in many countries that have a Mediterranean climate such as California. Thus, the spread of the virus throughout California must be considered as a serious potential threat to the tomato industry.

There are a number of factors why it has not yet spread to all the major tomato-producing areas of California, including the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys. First, its vector, Bemisia whitefly species are not typically found in these tomato-producing areas because it is intolerant of winter temperatures there. Second, the Central Valley’s winter season provides a ‘natural’ tomato-free period, which usually goes from late November through early February. Although the virus can infect other plants, tomato is the host in which it builds-up most quickly. Thus, by having an annual ‘tomato-free period’, it is likely that the amount of viral inoculum (as well as whitefly populations) will be significantly reduced by the time the tomato planting season starts again in late winter-early spring. This would mean that, even if the virus is able to overwinter, it may take a long time to reach levels that cause economic damage.

Management

Remember, prevention is often the best strategy for managing tomato plant diseases. Start with healthy plants, provide proper spacing, avoid overhead watering, maintain good air circulation, and practice proper sanitation. If you suspect a disease, it’s important to identify it accurately before applying any treatments. Local agricultural extension services can provide specific guidance based on your region’s conditions.

Learn More About Your Area of Interest Below